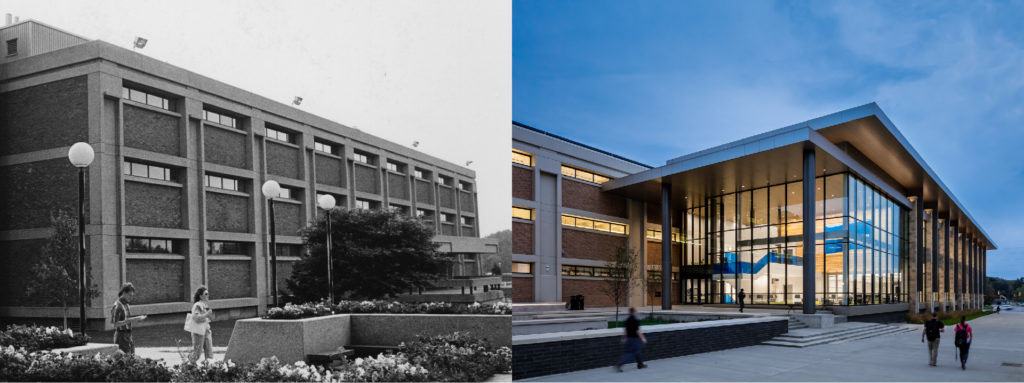

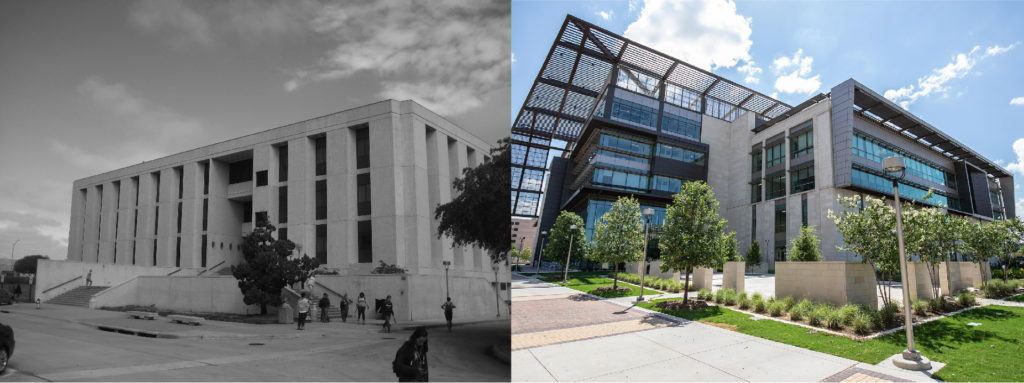

The post-WWII era brought a surge of construction to college campuses, fueled by the GI Bill, the Space Race, increased science research funding, and the demographic tsunami of the Baby Boomers. The building designs from that era demonstrate a range of characteristics: the textured surfaces of mid-century modern, the simplified structure of minimalism, or the stronger, more formalist voice of Brutalism. Often characterized by raw concrete construction of simple blockish forms, the buildings allowed institutions to project a forward-thinking sensibility and build significant structures economically.

The result was a sizeable and often challenging generation of campus development. Some buildings and landscapes from this era have stood the test of time in both beauty and functionality, but many have not.

Additionally, buildings and their infrastructure systems have a cycle of obsolescence, no matter the era of initial construction. They wear out over time, usually requiring reinvestment after about 30 years and certainly around 50. Even when the physical structure is sound, the activities that a building supports will change, as do safety regulations, programmatic best practices, and technological and design innovations.

Today, many universities are at a crossroads regarding what to do with these buildings. Is the wisest choice to reinvest in existing buildings and their infrastructure systems? Are there effective ways to renew or repurpose these structures? Or is the best choice to rebuild?

The first step in answering these questions is to start with an objective assessment of the building: architecture, engineering, cost, land value, campus planning, strategic initiatives, and historic preservation. Information about the building’s existing conditions can be developed in layers, increasing in detail as likely scenarios come into focus. Some key factors to consider are the integrity of the facility’s structural systems, and if its floor-to-floor heights allow for modern mechanical and electric infrastructure. (For a deeper dive on this part of the process, I recommend this recent article from The Chronicle of Higher Education, “How to Make Old Campus Spaces Feel New Again.”)

Once the assessment is complete, options develop: what is possible, what will result in a great building, what implementation strategy works, and how it will be financed.

While no two situations are alike, we do see consistent themes (and solutions) on how to approach challenging decisions about the use of these existing buildings in our practice. As more institutions face decisions about how to handle mid-century buildings, the following case studies provide progressive and forward-leaning strategies that make investments in current students and in future generations.