Recently, I presented at the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE) Conference in Spokane, Washington on the opportunity of regenerative design and the circular economy as it relates higher education projects and campuses. At the largest networking and educational event of its kind in North America, my session, titled “Defining the Finish Line: What the Circular Economy for Universities Should Look Like,” helped attendees understand how design principles extracted from the natural world can act as a guiding platform for colleges and universities to develop a circular economy on their campuses.

Sustainability as a concept is laudably a part of everyday discourse now. This prevalence, however, highlights the importance of non-complacency and continuing to think beyond. Sustainability is not an end unto itself, it is a mid-point on the spectrum of performance between degenerative and regenerative. We can do better, and it’s important to look to how our buildings can create a net-positive impact on the environment.

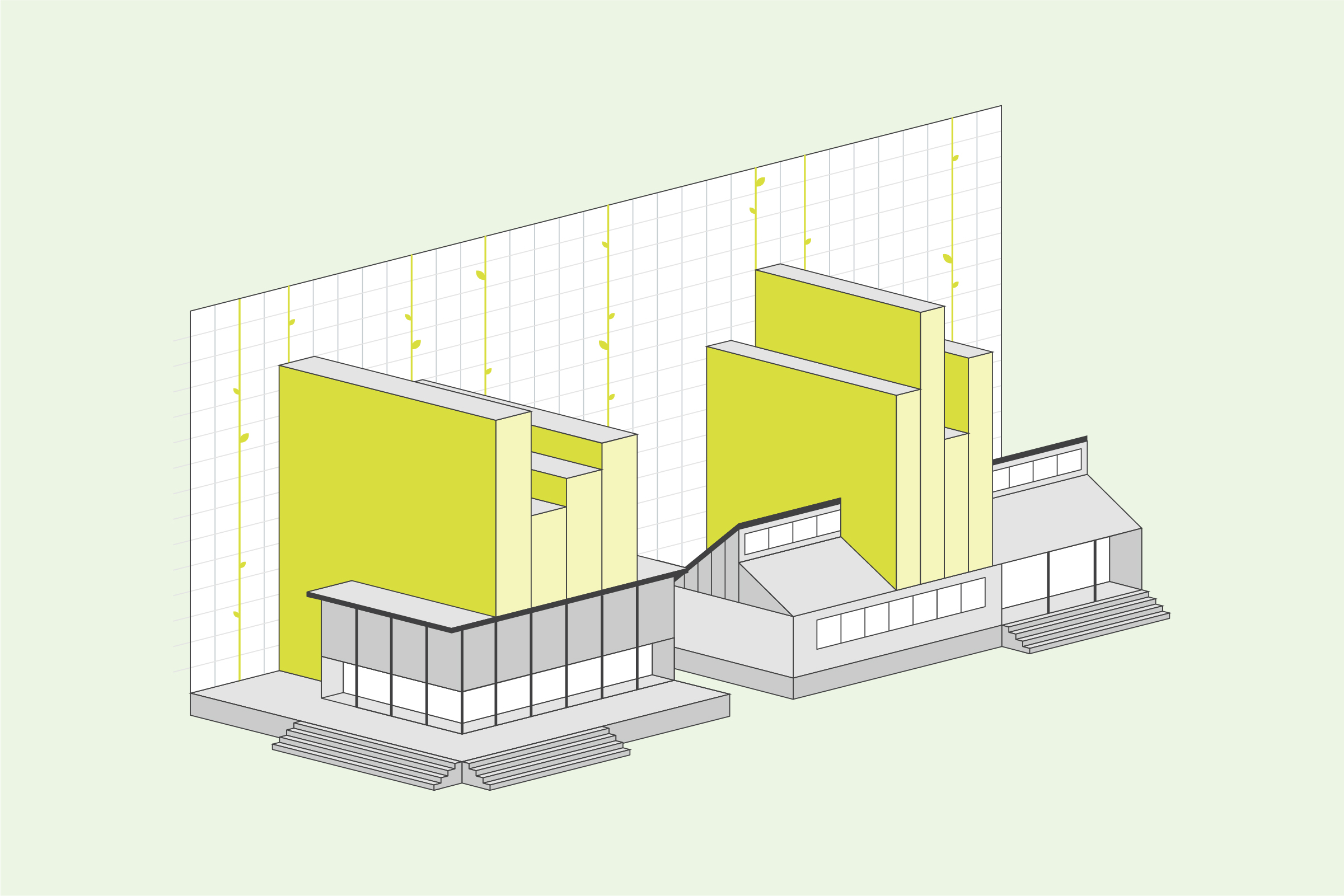

We needn’t look far. Processes occurring in the natural world provide an excellent toolbox. It is the job of architects and designers to translate these thoroughly time-tested concepts into the built environment. Principles outlined in Permaculture, a design practice developed by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren in Australia in the late 1970’s, do an excellent job of getting this conversation started. These concepts appear in many of our projects.