Across the cultural sector, there is a growing expectation that collections storage facilities — once hidden, highly protected back-of-house environments — should become places that showcase the value of collections care. Internationally, purpose-built collections centers are experimenting with innovative ways to offer controlled visibility, visitor programs, and new forms of engagement, all while maintaining high standards of preservation and security.

As a firm deeply engaged in collections planning and design, we have a particular interest in how these emerging practices influence the next generation of cultural infrastructure. We recently conducted a benchmarking study of collections facilities worldwide, including projects in our own portfolio such as Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory at Jefferson Patterson Park, the AlUla Collection Care Facility, and multiple Smithsonian Collections care centers. Based on that research we’ve synthesized what cultural institutions should consider as they look to balance three critical priorities: public access, collections care, and institutional security.

Starting with public access, we’ve found that for most cultural organizations, the vast majority of their holdings remain out of public view. According to the American Alliance of Museums, only 1% of natural history collections and 3–5% of art museum collections are typically exhibited. This disconnect challenges museums’ educational missions, visitor expectations, and has prompted institutions to rethink what collections storage can and should be.

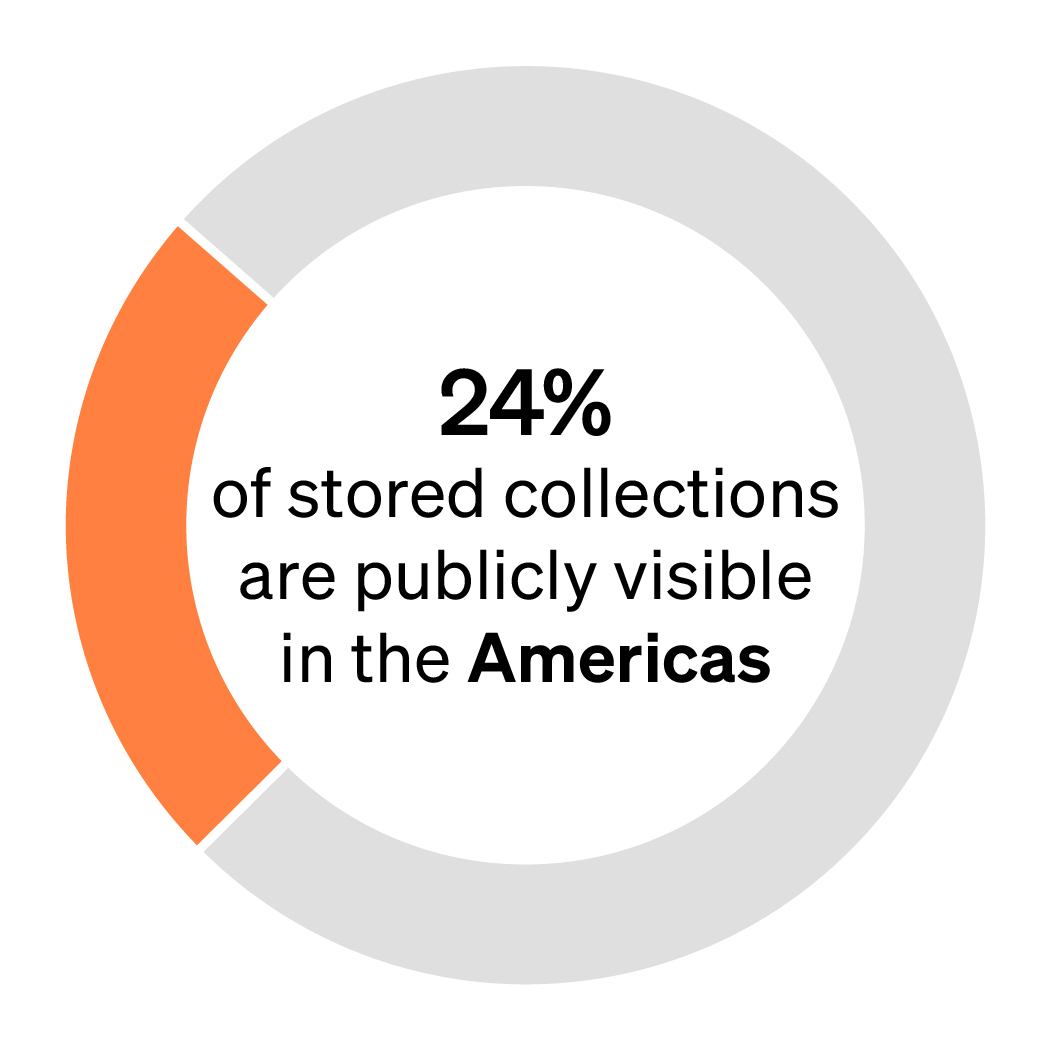

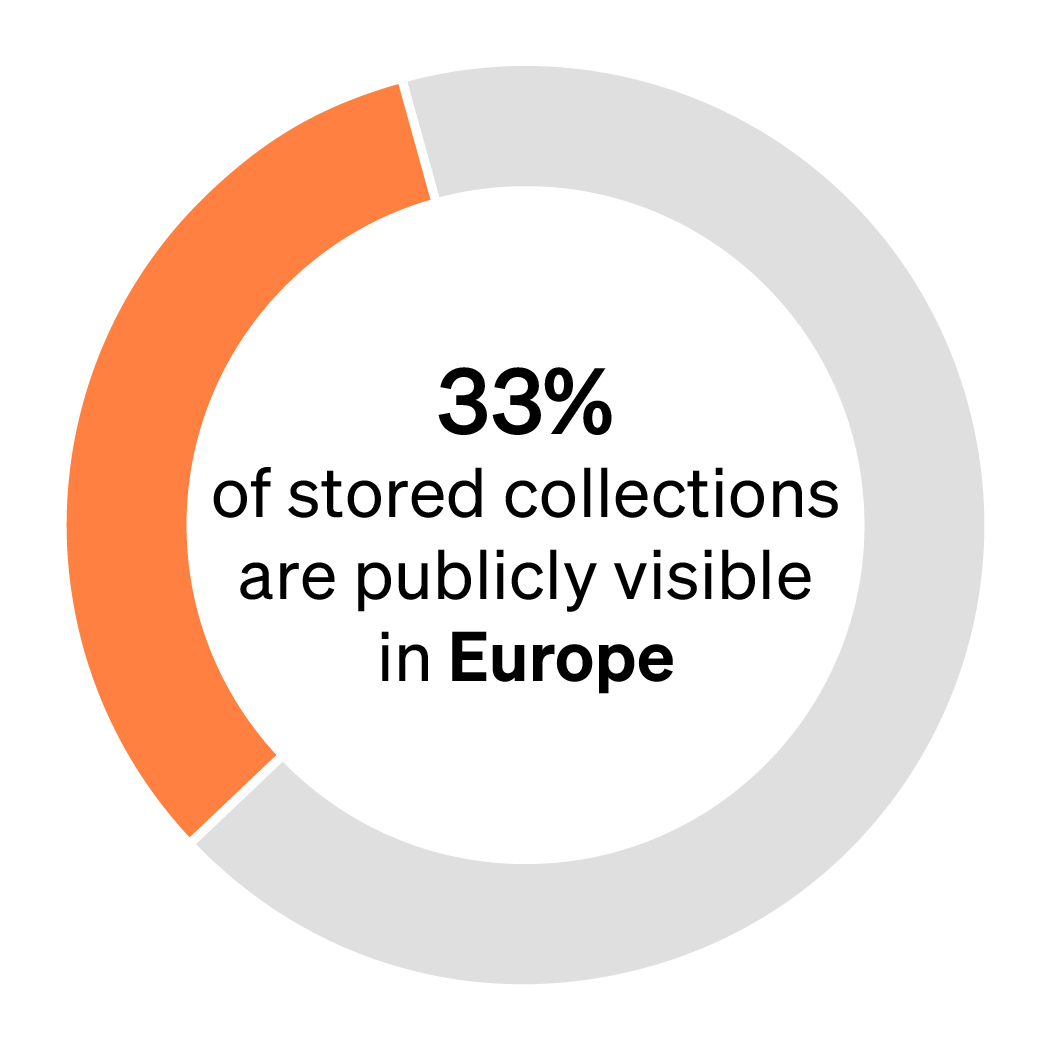

Our collections benchmarking has found that, on average, publicly accessible collections space constitutes about 12% of the total area across global facilities. However, within the United States, that figure drops dramatically to just 2%.