Several major technical challenges stand in the way of realizing this vision. First, conventional floating wetlands are costly, and yet they typically last a mere five years. It would be prohibitively expensive for the Aquarium to replace such a large floating wetland structure (planned to be 16,000+ SF) twice per decade.

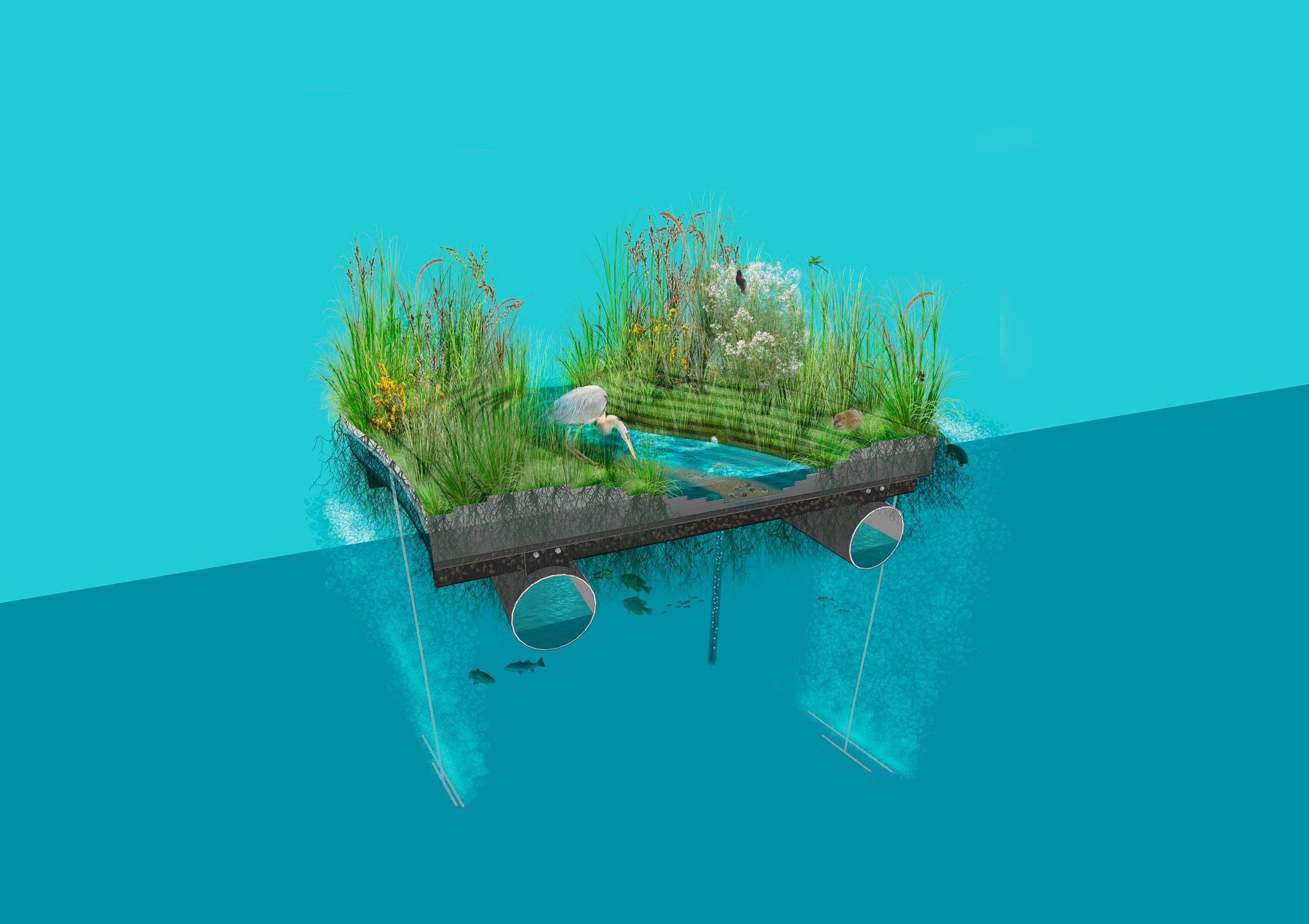

Secondly, conventional floating wetland systems are topographically flat and not readily calibrated to create a range of microhabitats. They are incapable of supporting the ecological diversity that the Aquarium desires for this unique environment.

Lastly, conventional floating wetlands are not stable enough to support maintenance personnel. For the Aquarium to be able to manage such a landscape, the structure needs to be designed with a high degree of stability.

To realize the client’s vision, our designers (and our partners at Biohabitats, McLaren Engineers, and Kovacs, Whitney & Associates, continuing Studio Gang’s EcoSlip concept) had to create a durable and more topographically varied floating wetland.

***

A brief history of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor: in pre-Columbian times, there was tremendous biodiversity in this zone of the Chesapeake Bay. With the rise of the Industrial Revolution, the area became a major shipping port. Hard infrastructure development mirrored rising urban populations into the early 20th century, replacing natural shorelines. Humans reshaped the harbor to suit the needs of industry and shipping, which resulted in lost habitats and waning species diversity.

The heavy industry eventually faded, and in the 1980s the Inner Harbor was one of the first post-industrial waterfronts transformed into a cultural amenity. Unfortunately, while the land surrounding the Inner Harbor’s water was revitalized, the water itself was largely neglected.

Another significant development that affects the health of the Chesapeake Bay is sprawling urbanization throughout much of its watershed. Hard surfaces cover soil and prevent infiltration of rain water into the ground, so when rain falls on buildings and pavement, it carries lawn fertilizers, pet waste, and road salts into storm drains. Leaks in an aging network of sewer and stormwater pipes, running underneath the city, also added excess nitrogen and phosphorous to Inner Harbor waters. This polluted urban stormwater runoff joins suburban and rural runoff and ultimately flows downstream into waterways like the Inner Harbor. Excess nitrogen and phosphorous, transported in polluted stormwater runoff, is utilized by naturally occurring phytoplankton species and fuels an endless cycle of algae population explosions and crashes throughout the Inner Harbor. When the excess fertilizers that enabled the algal blooms to occur are consumed, a massive die-off of phytoplankton follows. The dead algae sinks to the bottom and provides food that fuels a major bacterial bloom. The rapidly growing bacteria population uses up all the available dissolved oxygen in the water and effectively smothers fish, crabs, and other aquatic life.

Reversing years of environmental degradation and creating a renewed and thriving ecosystem requires a large-scale intervention capable of delivering a wide array of ecological services. Floating wetlands were a natural choice for the Aquarium’s project.

However, as noted above, conventional floating wetlands have some significant drawbacks. They are typically made of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) injected with marine foam for buoyancy. Plants are placed in drilled holes to allow their roots to reach directly into the water. The PET layers are typically flat with upper layers extending out of the water – a form that does not mimic the varied topography and microhabitats of most wetlands or tidal shorelines. Thus only a limited number of aquatic species can thrive in them (falling well short of the Aquarium’s ambitions for this project).

Additionally, with time, biomass accumulates from plants and bivalves that colonize the PET mesh, causing the entire wetland to sink under its own weight.

Therefore, while current models of floating wetlands can serve decorative and educational purposes, they are ultimately more akin to a flower show exhibit than to a real-life habitat that is both durable and functional enough to achieve the Aquarium’s objectives. We had to develop a new floating wetland model and adapt an array of technologies from other disciplines to realize our goals.

***

In collaboration with the Aquarium and our multidisciplinary team of scientists and engineers, we designed a new kind of floating wetland. It improves upon the technologies of conventional floating wetlands while remedying their shortcomings in terms of habitat-creation capabilities and the lifespan of the final installation. These new technologies and variables have been prototyped and are currently being tested within the harbor on the Aquarium’s campus.