This site uses cookies – More Information.

National Aquarium Floating Wetland Prototype Wins ASLA Honor Award for Research

An innovative, high-performing floating wetland prototype, created by Ayers Saint Gross for the National Aquarium, won a 2018 American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) Honor Award for Research.

“I’m so pleased to see our wetland prototype honored by ASLA,” Ayers Saint Gross associate principal Amelle Schultz said. “Reimagining existing technologies with a team of engineers and curators to create a more resilient and functional floating wetland with the ability to improve the biodiversity and water quality of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor was a very rewarding challenge.”

The National Aquarium sits on an urban waterfront. The organization is well positioned to be an agent of change for urban water quality, given its national leadership position in conservation science and restoration. With the ultimate goal of transforming its campus into a living laboratory, the Aquarium teamed with designers, engineers, and researchers to investigate new technologies to produce a better floating wetland.

“The innovative fusion of technology and design in this wetland development, and the collaboration with organizations like Ayers Saint Gross, creates a model for acting on our mission to protect and conserve aquatic treasures,” said Jacqueline Bershad, VP of Planning and Design at the National Aquarium. “We are proud of the success of this prototype and look forward to making continual progress in transforming not only our own waterfront campus, but the health of the harbor and its inhabitants that form our urban ecosystem.”

Over the past decade, the concept of floating wetlands has gained traction in urban areas where native habitats have severely deteriorated as a low-cost opportunity to introduce native species back into aquatic habitats. However, the simple design and short lifespan of typical floating wetlands don’t offer a truly sustainable solution for urban waterfronts.

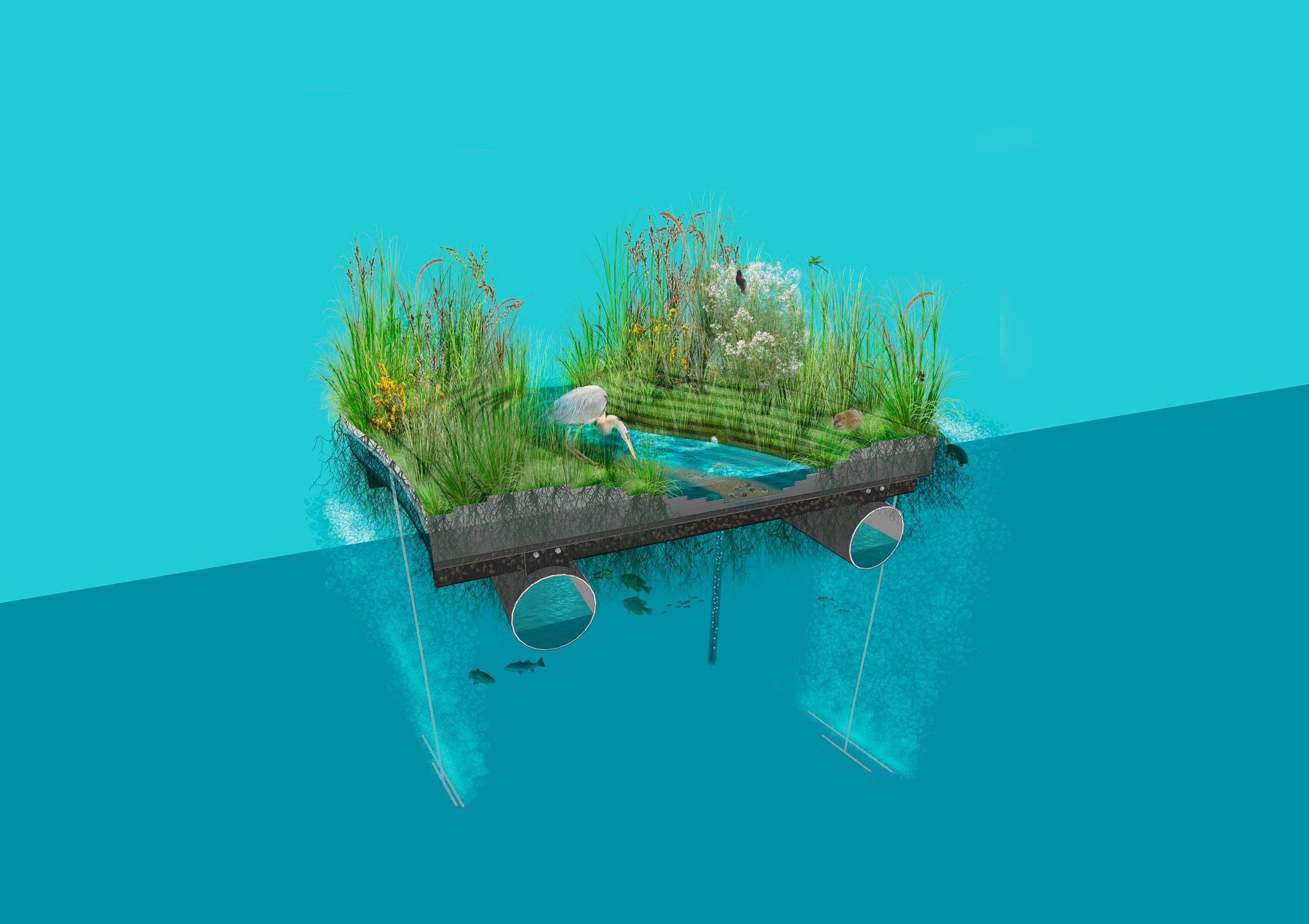

In collaboration with the Aquarium, our multidisciplinary team of in-house landscape architects, supplemented with scientists and engineers from Biohabitats, McLaren Engineering Group, and Kovacs, Whitney & Associates, designed a new kind of floating wetland. It improves upon the technologies of conventional floating wetlands while remedying their shortcomings in terms of habitat-creation capabilities and the lifespan of the final installation. These new technologies and variables have been prototyped and are currently being tested in the harbor on the Aquarium’s campus.

“We are encouraged by the progress and success this new floating wetland model shows in this prototype stage. We have seen schools of fish, like Atlantic silversides and killifish, and have also had two successful nesting mallard ducks. It is reassuring to see the local wildlife utilize this natural habitat while in an urban city,” said Charmaine Dahlenburg, Chesapeake Bay Program Manager at the National Aquarium. “We continue to work collaboratively to adjust and perfect this model and see a future where more floating wetlands can transform the waterfront and make a true difference in our harbor.”

The floating wetland prototype is one of several collaborations between the National Aquarium and Ayers Saint Gross. The Waterfront Campus Plan, created in collaboration with our teammates at Biohabitats, McLaren Engineering Group, and Kovacs, Whitney & Associates as a continuation of Studio Gang’s EcoSlip concept, is a revitalization project that sets a precedent for waterfront development planning in urban sites. The firm’s landscape architecture studio also worked with our graphic design studio to create a bird-strike prevention graphic applied to the existing architecture in identified trouble areas.

“The National Aquarium’s mission of inspiring conservation of the world’s aquatic treasures is an important one, and the wetlands prototype is an exciting example of how landscape architecture can contribute to that mission,” Schultz said. “We are eager to continue our research, and implement more of the Waterfront Campus Plan in an effort to make the site a true living laboratory.”